Local governance in China, West differs

The elections in countries that call themselves liberal democracies seem never-ending. Regular or early elections, from presidential to parliamentary and local, create the illusion that "something is happening". But it is all merely a fa?ade, a recycling of the same, visibly inefficient and desperately flawed, politics. Citizens are told that elections are a "celebration of democracy", masking the truth that democracy is lived every day, if it exists at all, not just when one steps into a voting booth. The quality of daily life is the true measure of democracy, but whatever remains of democracy is fast fading into insignificance.

North Macedonia is just one of many countries holding local elections this year at the municipal level. Political parties are drafting their election programs, gauging public opinion, compiling lists of citizens' demands translated into campaign promises, and even launching pre-election campaigns to win public support. While working on a joint project with colleagues from China, a thought crossed my mind: how does such a vast country address local issues?

In other words, what is considered "local" in such a context? I asked my younger colleague from Shanghai what is meant by local governance in China. In reply, he said: "What exactly do you mean by 'local'?" After all, my country, North Macedonia, is all of 25,000 square kilometers with barely 2 million people, which could be a "local community" in China.

He then explained that the term "local" in China carries multiple meanings. First, in relation to governance, "local" refers to a government multiple levels below the central government, including provincial, municipal and district governments. A local government comprises an administrative structure supported by the central government, but it maintains a certain degree of autonomy depending on the context.

Second, geographically speaking, "local" may refer to a specific region, province or city. For instance, "local" may refer to regional culinary traditions such as Sichuan, Cantonese and Yunnan. Economically, it signifies "domestic" or "regional" as opposed to imported.

Additionally, local businesses might be those operating within a single province or city rather than on a national scale. In political discourse, when Chinese leaders discuss "local" reforms or development, they usually mean policies implemented at the provincial, municipal or rural community levels.

In North Macedonia, it is often unclear what is local and what is national. More often than not, in many local people's eyes local governance is "feudalized" by some local sheriff who wins an election thanks to party influence and oligarchic power, with little concern for citizens' voices. It also means political fragmentation, division along ethnic or political lines. There is no coherent social system or harmony, whereas harmony and social order are what sustain a country as vast as China.

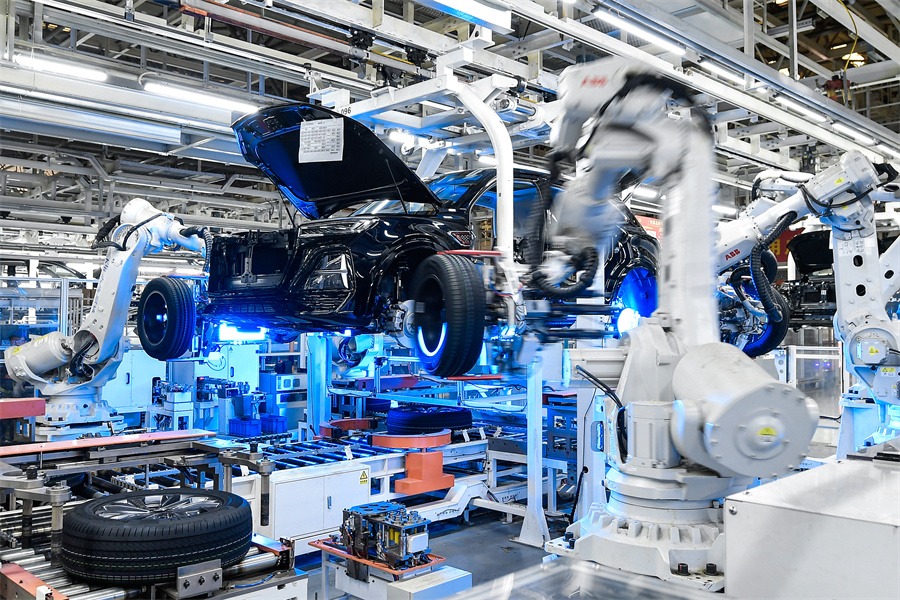

I visited at least four cities in China last year. My first impression was how orderly and clean everything was. Residential complexes in China are self-sustaining units, providing their inhabitants with everything they need within walking distance.

With my Western-influenced mindset, my first concern was security. Perhaps people live in concentrated residential communities to protect themselves from theft or other risks. But my hosts laughed, with one of them saying: "No, our nation is built on the foundation of community and collectivity, from the lowest to the highest levels."

It reminded me of our lost tradition of neighborly connection — the karshi kapidzhik — the neighbor's door directly across from yours, which you could knock on anytime, whether for good or bad reason. We've lost this tradition because of Western-style alienation, self-isolation and detachment.

My Shanghai colleague said that the National People's Congress, China's top legislature, was focused on devising policies to improve the quality of people's lives across the country. Unlike the West, which has become "individualistic" and failed to build communities, in China, the collective spirit is nurtured.

In China's vast network of communities, provinces, municipalities and districts, the focus is on the collective good. Unlike the West, there is no system collapse or lawlessness in China. Chinese authorities value both unity and diversity, so instead of a uniform approach, they adopt policies to promote or even experiment with local initiatives at a local level before implementing them nationwide. Agricultural reforms, and urbanization and environmental protection policies are frequently tested in this way. The local Party and administrative structure is solid yet responsive to challenges, resolving local issues through a "network of mediators".

A particularly charming aspect of local engagement in China, as my Shanghai friend said, is the presence of "aunts from the neighborhood committee" (usually retired women overseeing day-to-day matters in residential complexes). In rural areas and smaller cities, public meetings are regularly held, local officials are openly criticized, and citizens' petitions convey their dissatisfaction to higher authorities.

Zhang Weiwei, a professor at Fudan University, has elaborated on this issue. He emphasized the concept in his talk, "selection plus election", in the North Macedonian capital of Skopje last year. Within the Communist Party of China's structure, there is the spirit that drives officials to be competent, accessible and to gain public trust. And before advancing politically, officials have to prove their ability in local communities. One cannot lead a country without first proving oneself in a district or province — for at least two successful terms.

A Macedonian friend who has lived in China for many years shared an interesting fact with me.

He said that contrary to stereotypes of "authoritarianism" and centralized power at the "top", China also has a key "decentralized" feature.

The 2025 Chinese national budget data showed the central government's transfer payments to local governments will reach 10.34 trillion yuan, exceeding 10 trillion for the third consecutive year. Fiscal transfer payments are taken from developed provinces and used in underdeveloped regions to address regional fiscal imbalances and promote equalization of basic public services.

In contrast, in the United States, a so-called "federation", the ratio between central and local financial distribution is about 50 to 50, and in European countries, on average, the distribution is 80 to 20 in favor of the central government. This shatters the myth of Western European democracies being champions of local self-governance.

In this regard, China's self-governance model is efficient and effective. China may not be a democracy based on party struggles and political discord, but it is a democracy that focuses on solving problems, moving forward and improving people's lives and livelihoods.

The author is a professor of international relations and peace studies at the Institute for Security, Defense, and Peace, Faculty of Philosophy, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, North Macedonia.

The views don't necessarily represent those of China Daily.

If you have a specific expertise, or would like to share your thought about our stories, then send us your writings at opinion@chinadaily.com.cn, and comment@chinadaily.com.cn.